Regina Parra

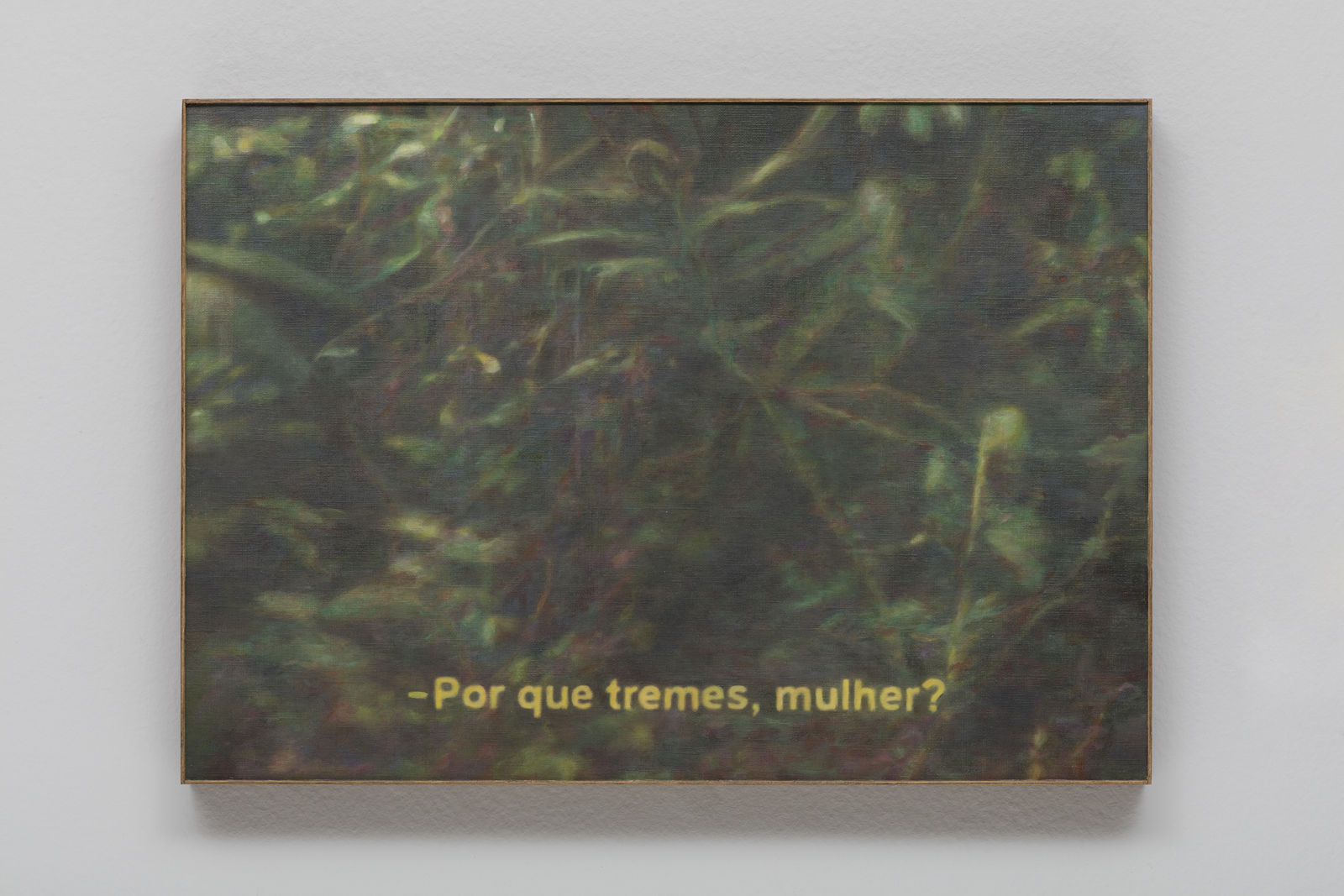

why are you trembling, woman?

Text by Moacir dos Anjos, curator of the solo show at Galeria Millan, 2016

Regina Parra’s exhibition does not formulate an idea that is delivered at once. It is more an environment that resonates diffuse annoyances than a collection of things with precise meanings. Considering each of the works on display isolated, it is not immediately clear what moved the artist to create them as a whole. From the interrogative title of the show—Why are you trembling, woman?—there is a deliberate bet on the imprecision of what is communicated, as if only through the opacity of the language employed it would be possible to speak clearly. It is only when one goes from one work to the other that a web of senses is woven in a sort of ricochet between paintings, drawings, video, text, and audio.

Here, the sounds matter as much as the images, promoting synesthetic operations. The repeated listening of the expression “yes, sir” and other similar ones—isolated by the artist from their original contexts and chained in a sonorous narrative—evokes situations of assent to the speech of those who have the power to command. A type of obedience that immobilizes and regulates bodies, inscribing in them, as if they were natural, movements that express agreement with the given orders. Automated body responses as the drawings by Parra suggest, which appear to belong to old gymnastics manuals. But, instead of the variety of gestures, the only movement taught in the artist’s works is one of the head which repeatedly moves up and down: a clear signal of obedience to what is commanded.

Besides the sounds that refer to images that were subtracted from the viewer, there are paintings that describe absent sculptures, in a continuous process of replacement of immediate referents. These paintings evoke representations of blacks, indians and women in sculptures commonly found on colonial farms in the states of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. Sculptures that have French or Italian origin and are generally called blackamoor, having as main characteristic the presentation of these men and women in situations of subservience, although always with the docile appearance of those who do not have will and are resigned or satisfied in being a servant.

Therefore, the sounds and images presented by Parra arise in a discrete, but still loquacious way, the marks of the violence that rules the history of Brazil—the remote as the recent. Violence that reaches blacks and indians in full, and which has in women (including white ones, who are therefore a little black and indian) one of their most frequent targets, as suggested by the question that gives name to the exhibition. “Why are you trembling, woman?” is a verse from poet Castro Alves that describes the fear of a woman enslaved whose small son will be sold. Fear of loss of something important that is quiet similar to those felt by many Brazilian women in situations of violence against them or their children. The enclosed forest is portrayed in a large painting, a symbolic projection of what lies beyond what the eye reaches and which causes fear because it is not a known territory.

This paradox anchors the video Captain of the Forest, entitled after the bird that inhabits many of the forests of Latin America and that in the past gained such nickname by announcing, with its sharp song, any strange movement in the bush, revealing fugitive slaves that tried to hide in the woods. In a landscape as exuberant as claustrophobic, the artist brings together bird song and sound coming from the mouth of man, in a staged remembrance of this improbable and deadly alliance. A pair of small paintings finally portrays a bird inert on the ground: the one who cries is now silent and dead. Other captains of the forest, however, still insist on their pursuit of persecution.

In the last change and twist of the media, Parra writes and inverts, in neon lights, phrases that announce options of how to behave regarding the pain of the others, long ago enunciated by the martinican essayist Frantz Fanon: to remain terrified or to become terrible. However, it is not for her work to induce any clear position. This is not its responsibility, and it is up to each one whether or not to be affected by this sketch of an archeology of Brazilian violence that the artist presents. That is all that Art can offer to combat what is unbearable for many people. And it is already a lot.

Moacir dos Anjos is senior researcher and curator at Fundação Joaquim Nabuco and was director of Museu de Arte Moderna Aloisio Magalhães (MAMAM), in Recife. He was a visiting research fellow at TrAIN research center of the University of the Arts, London (2008-2009). And curated the Brazilian Pavilion at 54th Venice Biennale (2011), the 29th Bienal de São Paulo (2010).

Exhibitions

Why are you trembling woman?, curated by Moacir dos Anjos, Galeria Millan, Sao Paulo, Brazil